Perceived environmental change and community resilience in Westfjords

22 December 2025

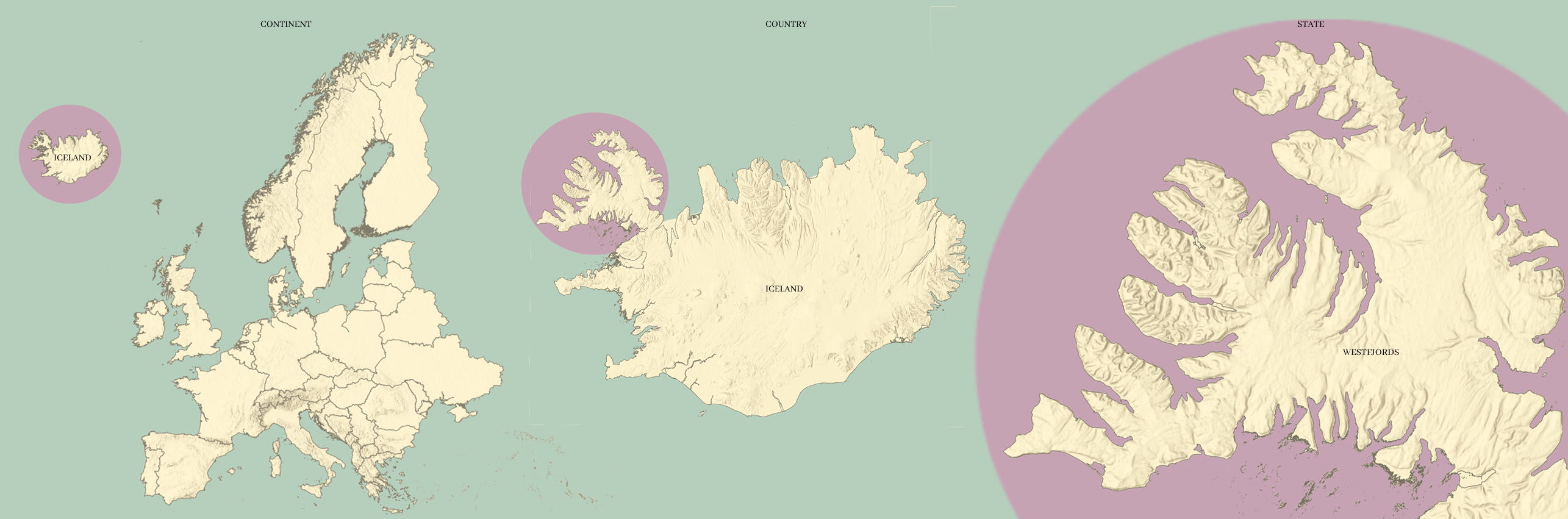

The peninsula of the Westfjords of Iceland is in the country’s north-west. With a population of just around 7,000, located in scattered settlements surrounded by high coastal mountains and fjords, it is one of Iceland’s most geographically isolated and sparsely populated regions. Natural hazards are a persistent challenge in the Westfjords. In collaboration with FutuResilience, research master’s students from the University of Groningen conducted a study to better understand the local community’s perceptions of climate-related risks, vulnerabilities, and resilience on the island.

Approach

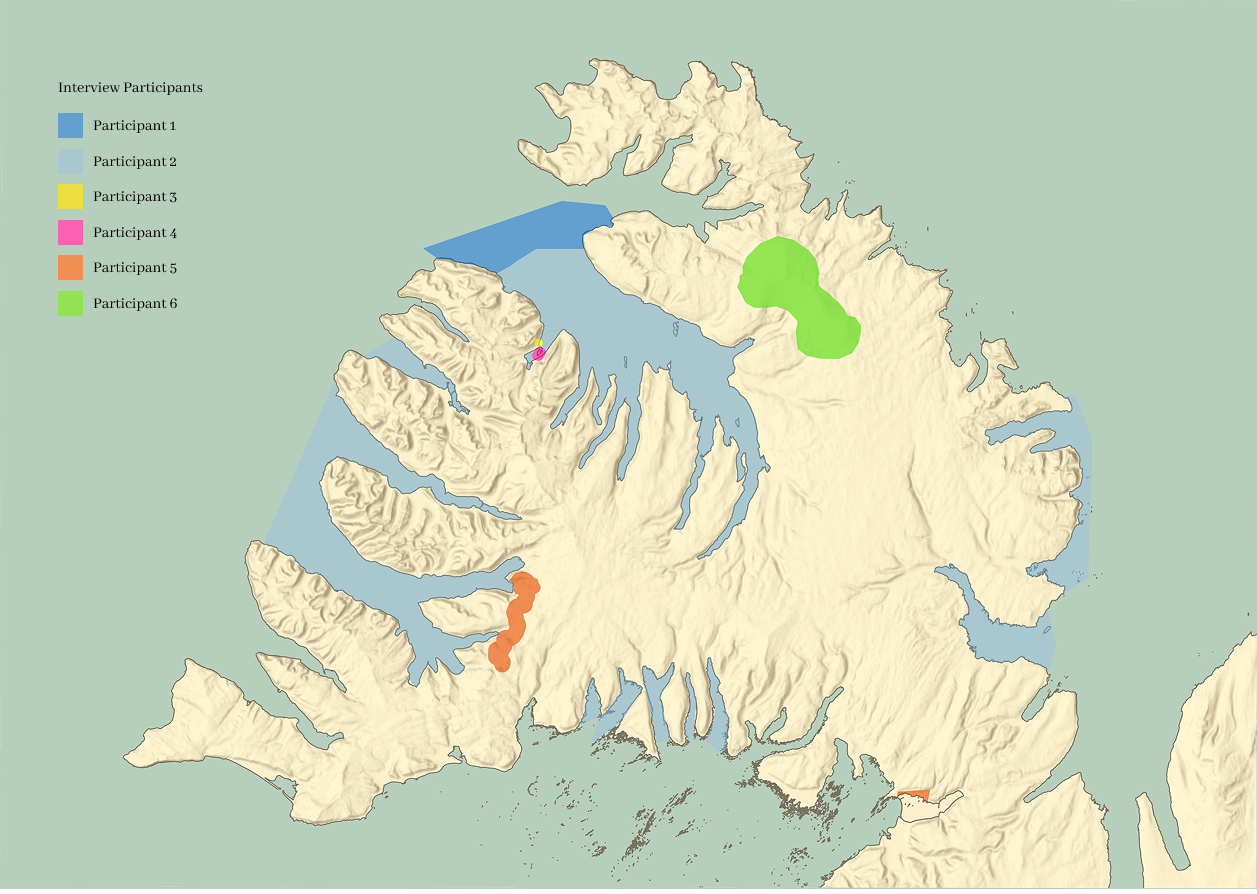

This study employed a qualitative, mixed-methods approach combining semi-structured interviews with digital participatory mapping (PPGIS). Primary data were collected through six online semi-structured interviews with seven local stakeholders in the Westfjords, including residents, tourism professionals, and fisheries experts. The interviews explored perceptions of environmental and socio-economic change, risk, and adaptation. Interview data were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis in Atlas.ti, while spatial data were processed and visualised using ArcGIS Pro. The integration of thematic and geospatial analysis enabled a spatially grounded understanding of local perceptions and resilience.

The participatory mapping exercise was a central component of the interview. Immediately following the narrative interview, participants engaged in Digital Participatory Mapping (PPGIS). The data collection platform used was ArcGIS Survey123, a web-based form application designed for ease of use and the capture of location data. Spatial data derived from the participatory mapping exercise (polygon features) and qualitative discourse data from the interviews (place references) were processed using GIS software, specifically ArcGIS Pro, to produce two complementary maps.

Analysis

1. Environmental changes perceived by the community

Community members in the Westfjords perceive environmental change primarily through transformations in the marine environment. Changes in fish migration patterns—particularly for capelin and cod—are widely observed and frequently discussed, alongside declining shrimp stocks and fluctuating quotas that contribute to economic uncertainty in fisheries. At the same time, the arrival of new species such as mackerel is often framed as a potential opportunity rather than solely a threat. Marine mammal populations are also perceived as shifting, with humpback whales increasing in number while minke whales appear to be declining. These changes reinforce a strong perception that the ocean is undergoing systemic and region-wide transformation.

Terrestrial environmental changes are perceived as more selective and spatially localised. Mudslides are commonly described as increasing, whereas avalanches and landslides are viewed as long-standing hazards rather than newly emerging risks. The retreat of the Drangajökull glacier is a prominent concern, with community members linking its shrinkage to downstream effects on marine ecosystems through increased freshwater runoff. In contrast to the broad marine changes, terrestrial impacts tend to be mapped to specific places such as glaciers, roads, or settlements.

Weather patterns are widely described as becoming more unpredictable, with residents noting decreased snowfall, fewer snow-rich winters, and more volatile seasonal transitions. Extreme weather events are perceived as occurring more frequently, and the loss of predictable seasonality is a recurring concern across interviews. Overall, environmental change is understood as spatially uneven: marine changes are experienced as expansive and systemic, while terrestrial and infrastructural risks are localised. Coastal and marine spaces therefore dominate community perceptions of environmental risk.

2. Societal changes in the Westfjords

Societal change in the Westfjords is closely tied to economic transformation, particularly in fisheries, tourism, and aquaculture. Fisheries remain central to local identity but are increasingly seen as economically fragile due to quota volatility and ecological change. Tourism has expanded rapidly and is widely viewed as economically beneficial, with cruise tourism in particular enabling year-round business activity and employment. Aquaculture is increasingly perceived as an important new economic pillar, contributing to diversification and future economic stability.

Infrastructure development is widely regarded as one of the most positive societal changes in the region. Improved roads and tunnels have increased safety, accessibility, and connectivity, reducing isolation and supporting both tourism and everyday life. At the same time, demographic shifts are altering traditional livelihoods, as younger Icelanders are less likely to enter fisheries-related professions. This has led to emerging skills shortages in marine and fisheries sectors and increased reliance on foreign workers, particularly in fisheries and tourism. The growing internationalisation of the population is further reinforced by tourism and the university in Ísafjörður, with language skills—especially English—playing an increasingly important role in employment opportunities.

3. Risk perception

Risk perception varies significantly among community members. High levels of concern are expressed around fisheries decline, ecosystem disruption, tourism pressure, and energy insecurity. Other environmental changes are perceived as distant or abstract and therefore less threatening to daily life. Many residents emphasise that economic and policy decisions often have a greater immediate impact on their lives than environmental change alone, shaping how risks are prioritised and understood. 4. Adaptive Capacity Observed Adaptive capacity in the Westfjords is characterised by strong diversification and everyday coping strategies. Residents frequently shift between fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism, and environmental change is often reframed as an economic opportunity—for example through whale watching or the arrival of new marine species. A strong cultural emphasis on “working around” challenges underpins local resilience, supported by institutional adaptations such as avalanche protection measures, fisheries regulations, and investments in tourism infrastructure. Despite this capacity, community members identify several needs to strengthen long-term resilience. These include improved access to clean energy and greater energy security, infrastructure investment tailored to the realities of remote regions, more locally sensitive national policies, increased investment in education, innovation, and long-term job creation, and stronger community engagement and awareness around ongoing environmental and societal change.

Preliminary Findings

- -Economic diversification underpins resilience: the shift from fisheries towards tourism and aquaculture has helped the Westfjords absorb environmental and economic shocks.

- Strong community cohesion enables adaptation: place attachment, social networks, and a “make-do” culture support everyday resilience.

- Infrastructure investment reduces vulnerability: improved roads, tunnels, and hazard protection have increased safety, accessibility, and quality of life.

- Structural vulnerabilities persist: dependence on climate-sensitive sectors, remoteness, and centralised policymaking constrain long-term resilience.

- Risk perception gaps matter: differences between local experience and scientific assessments influence how risks are prioritised and managed.

The Westfjords demonstrates adaptive capacity through economic diversification, infrastructure investment, and strong social cohesion, yet remains structurally vulnerable due to resource dependence, governance marginalisation, perception gaps, and rapid unregulated change. Economic shifts from fisheries towards tourism and aquaculture have spread risk, but these sectors remain sensitive to external shocks, while differing perceptions of environmental change and historical mistrust between scientists and fishing communities hinder collective, evidence-based adaptation. Centralised governance further constrains local resilience, as rural communities lack the resources and authority to implement context-specific solutions. Overall, resilience in the Westfjords is an ongoing negotiation among economic, environmental, cultural, and governance pressures. The region’s future depends on rebuilding trust, refining diversification strategies to reduce vulnerability rather than shift it, and enhancing local control over adaptation decisions.

*Article prepared by Blanquet Aguilar Samuel, Braun Max, Horlacher Patricia, Mazon Redin Johny, Ng Yiu Teng, Xu Yichen - as part of a Commissioned Research in collaboration with the University of Groningen.

Login to add a new comment